VOGUE versus VOQUE, “strike a pose VOGUE, VOQUE, VOGUE…”

I know what you’re thinking…it’s only her second week and Fash Tech Lawyer has committed the blogger’s cardinal sin, a typo! Or not…

As I sit here bleary eyed after a looooooong night reviewing a laborious software agreement and sipping a double espresso, I find myself having to double take. Am I going mad? Am I seeing this right? Does that say “VOQUE“ or “VOGUE“?!

Condé Nast’s opposition

VoQue Limited is a wholesale fashion company with a UK registered office. The company is two years old and reported a 2014 turnover of £10,000.

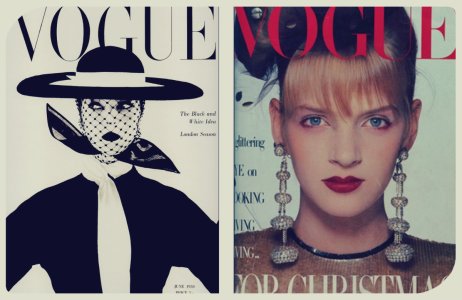

In September 2013 it applied to register the logo below as a UK trade mark for leather goods; clothing, footwear and headgear. As we know from the Louis Vuitton case (posted here last week), once a trade mark is registered, it will enjoy a presumption of validity until challenged. However, sadly for VoQue it didn’t get that far…

Hot on VoQue’s heels, the fashion bible VOGUE was not too happy about this and quickly opposed the VOQUE application in December 2013.

Condé Nast, which owns VOGUE, said that the VOQUE mark:

• is confusingly similar to VOGUE, and if registered or even used, would take unfair advantage of VOGUE’s success (if you’re really interested, the relevant law can be found under Section 5(2) (b) and 5(3) of the Trade Marks Act 1994); and

• would cause misrepresentation and damage to the holier than thou publication under Section 5(4)(a) of the Act!

VoQue bites back

In response to this, VoQue said:

• VOQUE and VOGUE carry out totally different activities;

• the typeface used by the VOQUE mark is completely different to the VOGUE mark; and

• VOQUE means “evoke” or “awaken” in French and is different to VOGUE’s “fashionable” or “popular” meaning.

Drum roll please….and it was decided…

No surprises, Condé Nast’s opposition was upheld. Nice try VoQue!!

In July 2015 a decision in favour of the fashionistas’ handbook said:

• the two marks are confusingly alike and have an overall degree of visual, aural and conceptual similarity; and

• VOGUE is distinctive given its reputation and the fact it is not entirely descriptive when used on the iconic publication.

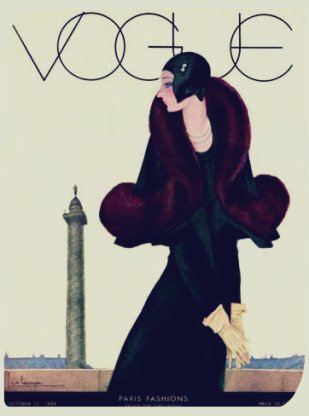

Founded in 1892, Vogue has been at the forefront of fashion publications for well over 100 years! This example is from the 1920s Art Deco era.

The application for the VOQUE mark was therefore dismissed and VoQue Limited was ordered to pay the costs incurred by Condé Nast.

The decision also noted:

• the fact that VoQue’s mark has a large crown element around the letter “Q” does not matter, as the average shopper would not see it as sufficiently different;

• the word “Vogue” is a well-known English word meaning “in fashion” and when used in relation to leather goods and clothing, for which the VOQUE mark was registered, alludes to such goods being “of the moment”, which draws parallels between the two marks; and

• the typeface used by VoQue is not unusual, in fact, Condé Nast would be well within their rights to use their VOGUE mark in the same style.

Interestingly, had VoQue managed to slip this one past VOGUE (unlikely!) thereby obtaining registration status, only for VOGUE to then challenge the registered mark at a later date, VOQUE would have been revoked (ironic huh, or just a really bad joke!?)!

Final thought

After reading the case first and foremost, I’m pretty pleased I don’t need my eyes testing, but the lesson to learn from all of this is that it’s risky business basing your branding on a similar, earlier and well established registered mark. There’s only one VOGUE!